The Red Terror was a period of political repression and mass killings carried out by Bolsheviks after the beginning of the Russian Civil War in 1918. The term is usually applied to Bolshevik political repression during the whole period of the Civil War (1917–1922),[1][2] as distinguished from the White Terror carried out by the White Army (Russian and non-Russian groups opposed to Bolshevik rule) against their political enemies (including the Bolsheviks). It was modeled on the Terror of the French Revolution. The Cheka (the Bolshevik secret police)[3] carried out the repressions of the Red Terror.[4] Estimates for the total number of people killed during the Red Terror for the initial period of repression are at least 10,000.[5]Estimates for the total number of victims of Bolshevik repression vary widely. One source asserts that the total number of victims of repression and pacification campaigns could be 1.3 million,[6] whereas another gives estimates of 28,000 executions per year from December 1917 to February 1922.[7] The most reliable estimations for the total number of killings put the number at about 100,000,[8] whereas others suggest a figure of 200,000.[9]

Purpose

The Red Terror in the Soviet Russia was justified in the Soviet historiography as a wartime campaign against counter-revolutionaries during the Russian Civil War of 1918–1921, targeting those who sided with the Whites (White Army). Under the slogan "Who is not with us, they against us", Bolsheviks referred to any anti-Bolshevik factions as Whites, regardless of whether those factions actually supported the White movement cause. Leon Trotsky described the context in 1920:

The severity of the proletarian dictatorship in Russia, let us point out here, was conditioned by no less difficult circumstances [than the French Revolution]. There was one continuous front, on the north and south, in the east and west. Besides the Russian White Guard armies of Kolchak, Denikin and others, there are those attacking Soviet Russia, simultaneously or in turn: Germans, Austrians, Czecho-Slovaks, Serbs, Poles, Ukrainians, Roumanians, French, British, Americans, Japanese, Finns, Esthonians, Lithuanians ... In a country throttled by a blockade and strangled by hunger, there are conspiracies, risings, terrorist acts, and destruction of roads and bridges.

He then went on to contrast the terror with the revolution and provide the Bolshevik's justification for it:

The first conquest of power by the Soviets at the beginning of November 1917 (new style) was actually accomplished with insignificant sacrifices. The Russian bourgeoisie found itself to such a degree estranged from the masses of the people, so internally helpless, so compromised by the course and the result of the war, so demoralized by the regime of Kerensky, that it scarcely dared show any resistance. ... A revolutionary class which has conquered power with arms in its hands is bound to, and will, suppress, rifle in hand, all attempts to tear the power out of its hands. Where it has against it a hostile army, it will oppose to it its own army. Where it is confronted with armed conspiracy, attempt at murder, or rising, it will hurl at the heads of its enemies an unsparing penalty.

Martin Latsis, chief of the Ukrainian Cheka, stated in the newspaper Red Terror:

Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which class he belongs, what is his background, his education, his profession. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the Red Terror.

— Martin Latsis, Red Terror[10]

The bitter struggle was described succinctly from the Bolshevik point of view by Grigory Zinoviev in mid-September 1918:

To overcome our enemies we must have our own socialist militarism. We must carry along with us 90 million out of the 100 million of Soviet Russia's population. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.

— Grigory Zinoviev, 1918[11]

History

The campaign of mass repressions officially started as retribution for the assassination (17 August 1918) of Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky by Leonid Kannegisser and for the attempted assassination (30 August 1918) of Lenin by Fanni Kaplan. While recovering from his wounds, Lenin instructed: "It is necessary – secretly and urgently to prepare the terror".[12]Even before the assassinations, Lenin had sent telegrams "to introduce mass terror" in Nizhny Novgorod in response to a suspected civilian uprising there, and to "crush" landowners in Penza who resisted, sometimes violently, the requisitioning of their grain by military detachments:[2]

Comrades! The kulak uprising in your five districts must be crushed without pity ... You must make example of these people. (1) Hang (I mean hang publicly, so that people see it) at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers. (2) Publish their names. (3) Seize all their grain. (4) Single out the hostages per my instructions in yesterday's telegram. Do all this so that for miles around people see it all, understand it, tremble, and tell themselves that we are killing the bloodthirsty kulaks and that we will continue to do so ... Yours, Lenin. P.S. Find tougher people.

The Bolshevik communist government executed five hundred "representatives of overthrown classes" immediately after the assassination of Uritsky.[3]

The first official announcement of a Red Terror, published in Izvestiya, "Appeal to the Working Class" on 3 September 1918, called for the workers to "crush the hydra of counterrevolution with massive terror! ... anyone who dares to spread the slightest rumor against the Soviet regime will be arrested immediately and sent to concentration camp".[13] There followed the decree "On Red Terror", issued on 5 September 1918 by the Cheka.[14]

On 15 October, the leading Chekist Gleb Bokii, summing up the officially ended Red Terror, reported that in Petrograd 800 alleged enemies had been shot and another 6,229 imprisoned.[12] Casualties in the first two months were between 10,000 and 15,000 based on lists of summarily executed people published in newspaper Cheka Weekly and other official press. A declaration About the Red Terror by the Sovnarkom on 5 September 1918 stated:

...that for empowering the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission in the fight with the counter-revolution, profiteering and corruption and making it more methodical, it is necessary to direct there possibly bigger number of the responsible party comrades, that it is necessary to secure the Soviet Republic from the class enemies by way of isolating them in concentration camps, that all people are to be executed by fire squad who are connected with the White Guard organizations, conspiracies and mutinies, that it is necessary to publicize the names of the executed as well as the reasons of applying to them that measure.

— Signed by People's Commissar of Justice D. Kursky, People's Commissars of Interior G.Petrovsky, Director in Affairs of the Council of People's Commissars Vl.Bonch-Bruyevich, SU, #19, department 1, art.710, 04.09.1918[15]

As the Russian Civil War progressed, significant numbers of prisoners, suspects and hostages were executed because they belonged to the "possessing classes". Numbers are recorded for cities occupied by the Bolsheviks:

In Kharkov there were between 2,000 and 3,000 executions in February–June 1919, and another 1,000–2,000 when the town was taken again in December of that year; in Rostov-on-Don, approximately 1,000 in January 1920; in Odessa, 2,200 in May–August 1919, then 1,500–3,000 between February 1920 and February 1921; in Kiev, at least 3,000 in February–August 1919; in Ekaterinodar, at least 3,000 between August 1920 and February 1921; In Armavir, a small town in Kuban, between 2,000 and 3,000 in August–October 1920. The list could go on and on.[16]

In the Crimea, Béla Kun and Rosalia Zemlyachka, with Vladimir Lenin's approval,[17] had 50,000 White prisoners of war and civilians summarily executed by shooting or hanging after the defeat of general Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel at the end of 1920. They had been promised amnesty if they would surrender.[18] This is one of the largest massacres in the Civil War.[19]

On 16 March 1919, all military detachments of the Cheka were combined in a single body, the Troops for the Internal Defense of the Republic, which numbered 200,000 in 1921. These troops policed labor camps, ran the Gulag system, conducted requisitions of food, and put down peasant rebellions, riots by workers, and mutinies in the Red Army (which was plagued by desertions).[2]

One of the main organizers of the Red Terror for the Bolshevik government was 2nd-Grade Army Commissar Yan Karlovich Berzin (1889–1938), whose real name was Kyuzis Peteris. He took part in the October Revolution of 1917 and afterwards worked in the central apparatus of the Cheka. During the Red Terror, Berzin initiated the system of taking and shooting hostages to stop desertions and other "acts of disloyalty and sabotage".[4] As chief of a special department of the Latvian Red Army (later the 15th Army), Berzin played a part in the suppression of the Russian sailors' mutiny at Kronstadt in March 1921. He particularly distinguished himself in the course of the pursuit, capture, and killing of captured sailors.[4]

Repressions

Peasants

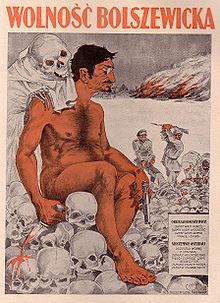

"Bolshevik freedom" – Polish propaganda poster with nude caricature of Leon Trotsky from the Polish–Soviet War

The Internal Troops of the Cheka and the Red Army practised the terror tactics of taking and executing numerous hostages, often in connection with desertions of forcefully mobilized peasants. According to Orlando Figes, more than 1 million people deserted from the Red Army in 1918, around 2 million people deserted in 1919, and almost 4 million deserters escaped from the Red Army in 1921.[20] Around 500,000 deserters were arrested in 1919 and close to 800,000 in 1920 by Cheka troops and special divisions created to combat desertions.[2] Thousands of deserters were killed, and their families were often taken hostage. According to Lenin's instructions,

After the expiration of the seven-day deadline for deserters to turn themselves in, punishment must be increased for these incorrigible traitors to the cause of the people. Families and anyone found to be assisting them in any way whatsoever are to be considered as hostages and treated accordingly.[2]

In September 1918, in just twelve provinces of Russia, 48,735 deserters and 7,325 bandits were arrested, 1,826 were killed and 2,230 were executed. A typical report from a Cheka department stated:

Yaroslavl Province, 23 June 1919. The uprising of deserters in the Petropavlovskaya volost has been put down. The families of the deserters have been taken as hostages. When we started to shoot one person from each family, the Greens began to come out of the woods and surrender. Thirty-four deserters were shot as an example.[2]

Estimates suggest that during the suppression of the Tambov Rebellion of 1920–1921, around 100,000 peasant rebels and their families were imprisoned or deported and perhaps 15,000 executed.[21]

This campaign marked the beginning of the Gulag, and some scholars have estimated that 70,000 were imprisoned by September 1921 (this number excludes those in several camps in regions that were in revolt, such as Tambov). Conditions in these camps led to high mortality rates, and "repeated massacres" took place. The Cheka at the Kholmogory camp adopted the practice of drowning bound prisoners in the nearby Dvinariver.[22] Occasionally, entire prisons were "emptied" of inmates via mass shootings prior to abandoning a town to White forces.[23][24]

Industrial workers

On 16 March 1919, Cheka stormed the Putilov factory. More than 900 workers who went to a strike were arrested, of whom more than 200 were executed without trial during the next few days. Numerous strikes took place in the spring of 1919 in cities of Tula, Orel, Tver, Ivanovo and Astrakhan. Starving workers sought to obtain food rations matching those of Red Army soldiers. They also demanded the elimination of privileges for Bolsheviks, freedom of the press, and free elections. The Cheka mercilessly suppressed all strikes, using arrests and executions.[25]

In the city of Astrakhan, strikers and Red Army soldiers who joined them were loaded onto barges and then thrown by the hundreds into the Volga with stones around their necks. Between 2,000 and 4,000 were shot or drowned between 12 and 14 March 1919. In addition, the repression also claimed the lives of some 600 to 1,000 of the bourgeoisie. Archival documents indicate this was the largest massacre of workers by the Bolsheviks before the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion.[26]

However, strikes continued. Lenin had concerns about the tense situation regarding workers in the Ural region. On 29 January 1920, he sent a telegram to Vladimir Smirnov stating "I am surprised that you are taking the matter so lightly, and are not immediately executing large numbers of strikers for the crime of sabotage".[27]

Atrocities

Excavation of a mass grave outside the headquarters of the Kharkov Cheka

At these times, there were numerous reports that Cheka interrogators used torture methods which were, according to Orlando Figes, "matched only by the Spanish Inquisition."[28] At Odessa the Cheka tied White officers to planks and slowly fed them into furnaces or tanks of boiling water; in Kharkiv, scalpings and hand-flayings were commonplace: the skin was peeled off victims' hands to produce "gloves"; the Voronezh Cheka rolled naked people around in barrels studded internally with nails; victims were crucified or stoned to death at Dnipropetrovsk; the Cheka at Kremenchuk impaled members of the clergy and buried alive rebelling peasants; in Orel, water was poured on naked prisoners bound in the winter streets until they became living ice statues; in Kiev, Chinese Cheka detachments placed rats in iron tubes sealed at one end with wire netting and the other placed against the body of a prisoner, with the tubes being heated until the rats gnawed through the victim's body in an effort to escape.[29]

Executions took place in prison cellars or courtyards, or occasionally on the outskirts of town, during the Red Terror and Russian Civil War. After the condemned were stripped of their clothing and other belongings, which were shared among the Cheka executioners, they were either machine-gunned in batches or dispatched individually with a revolver. Those killed in prison were usually shot in the back of the neck as they entered the execution cellar, which became littered with corpses and soaked with blood. Victims killed outside the town were moved by truck, bound and gagged, to their place of execution, where they sometimes were made to dig their own graves.[30]

According to Edvard Radzinsky, "it became a common practice to take a husband hostage and wait for his wife to come and purchase his life with her body".[3] During Decossackization, there were massacres, according to historian Robert Gellately, "on an unheard of scale". The Pyatigorsk Cheka organized a "day of Red Terror" to execute 300 people in one day, and took quotas from each part of town. According to the Chekist Karl Lander, the Cheka in Kislovodsk, "for lack of a better idea", killed all the patients in the hospital. In October 1920 alone more than 6,000 people were executed. Gellately adds that Communist leaders "sought to justify their ethnic-based massacres by incorporating them into the rubric of the 'class struggle'".[31]

Members of the clergy were subjected to particularly brutal abuse. According to documents cited by the late Alexander Yakovlev, then head of the Presidential Committee for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression, priests, monks and nuns were crucified, thrown into cauldrons of boiling tar, scalped, strangled, given Communion with melted lead and drowned in holes in the ice.[32] An estimated 3,000 were put to death in 1918 alone.[32]

Notes

- Melgounov (1975). See also The Record of the Red Terror.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), Chapter 4: The Red Terror.

- Radzinsky, Edvard (1997). Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives. Anchor. pp. 152–5. ISBN 0-385-47954-9.

- Suvorov, Viktor (1984). Inside Soviet Military Intelligence. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780026155106.

- Ryan (2012), p. 114.

- Rinke, Stefan; Wildt, Michael (2017). Revolutions and Counter-Revolutions: 1917 and Its Aftermath from a Global Perspective. Campus Verlag. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-3593507057.

- Ryan (2012), p. 2.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce (1989). Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War. Simon & Schuster. p. 384. ISBN 0671631667. ...the best estimates set the probable number of executions at about a hundred thousand.

- Lowe (2002), p. 151.

- Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future, 1994.

- Leggett (1986), p. 114.

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (2000). The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-14-028487-7, page 34.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 74.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 76.

- V.T.Malyarenko. "Rehabilitation of the repressed: Legal and Court practices". Yurinkom. Kiev 1997. pages 17–8.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 106.

- Rayfield, Donald (2004). Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him. Random House. p. 83. ISBN 0375506322. See also Stalin and His Hangmen.

- Gellately (2008), 72.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 100.

- Figes (1998), Chapter 13.

- Gellately (2008), p. 75.

- Gellately (2008), 58.

- Gellately (2008), p. 59.

- Figes (1998), p. 647.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), pp. 86–7.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 88.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 90.

- Figes (1998), p. 646.

- Leggett (1986), pp. 197–8.

- Leggett (1986), p. 199.

- Gellately (2008), pp. 70–1.

- Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev. A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-08760-8 page 156

- Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (2001), ISBN 0-8129-6864-6, p. 39.

- Robert Conquest, Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000), ISBN 0-393-04818-7, p. 101.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2008), p. 66.

- E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, Harmondsworth: Penguin (1966), pp. 121–2.

- Karl Marx, The Class Struggles in France (1850).

- Figes (1998), pp. 630, 649.

- Figes (1998), p. 525.

- Karl Kautsky, Terrorism and Communism Chapter VIII, The Communists at Work, The Terror

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), p. 82.

- Ryan (2012), p. 116.

- Ryan (2012), p. 74.

- Kołakowski, Leszek (2005). Main currents of Marxism. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 744–766. ISBN 9780393329438.

- Andrew, Christopher; Vasili Mitrokhin (2005). The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00311-7.

- Werth, Bartosek et al. (1999), pp. 73–6.

- Julius Martov, Down with the Death Penalty!, June/July 1918.

- After the War was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943–1960 (as an editor, Princeton UP, 2000)

- Denis Twitchett, John K. Fairbank The Cambridge history of China,ISBN 0-521-24338-6 p. 177

- BBC Article

- Banerjee, Nirmalya (15 November 2007). "Red terror continues Nandigram's bylanes". The Times Of India.

References and further reading

- Figes, Orlando (1998). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. Penguin Books. ISBN 0670-859168.

- Gellately, Robert (2008). Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf. ISBN 9781400032136.

- Leggett, George (1986). The Cheka: Lenin's Political Police. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822862-7.

- Lowe, Norman (2002). Mastering Twentieth Century Russian History. Palgrave. ISBN 9780333963074.

- Melgounov, Sergey (1975) [1925]. The Red Terror in Russia. Hyperions. ISBN 0-88355-187-X.

- Ryan, James (2012). Lenin's Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138815681.

- Trotsky, Leon (2017) [1920]. Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky. Verso. ISBN 9781786633439. See also text on marxists.org.

- Werth, Nicolas; Bartosek, Karel; Panne, Jean-Louis; Margolin, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Courtois, Stephane (1999). Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

External links

- Down with the Death Penalty! by Yuliy Osipovich Martov, June/July 1918

- The Record of the Red Terror by Sergei Melgunov

- More 'red terror' remains found in Russia UPI, July 19, 2010.